Establishing a Foreign-Invested Enterprise in Vietnam: The Definitive 2025 Guide

- 08/10/2025

CONTENT

CONTENT

CONTENT

CONTENT

Part I: The Investment Thesis for Vietnam: A Strategic Imperative

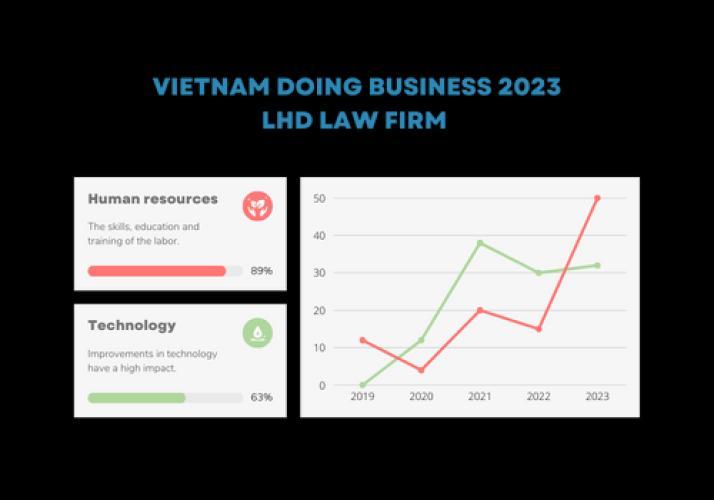

1.1 The Vietnamese Economic Ascendancy: Beyond the Hype

Vietnam has firmly established itself as a premier destination for foreign direct investment (FDI) in Southeast Asia, a status built on a foundation of consistent economic growth, political stability, and strategic integration into the global economy. The nation's economic performance demonstrates remarkable resilience and a clear upward trajectory. Following a period of global slowdown, the Vietnamese economy is showing distinct signs of recovery, with the World Bank forecasting GDP growth to reach 5.5% in 2024 and accelerate to 6.0% in 2025. The government's own ambitious targets project GDP growth of 8% or higher for 2025, signaling a strong commitment to fostering a pro-growth environment.

This optimism is substantiated by robust investment figures. In 2024, the total realized social investment capital was estimated at 3,692.1 trillion VND, a 7.5% increase from the previous year, reflecting a positive recovery in production activities. FDI disbursement in 2024 reached a record high, underscoring the sustained confidence of the international investment community. This trend has continued into 2025, with the first three months seeing nearly $10.98 billion in registered FDI, a 34.7% increase year-on-year, and disbursed capital reaching approximately $4.96 billion, up 7.2%. By the end of the first quarter of 2025, Vietnam hosted 42,760 active FDI projects with a total registered capital of $510.5 billion.

However, the narrative of Vietnam's appeal is undergoing a significant maturation. For decades, low labor costs were a primary driver of investment. While still competitive, this advantage is gradually being superseded by more sustainable and sophisticated factors. The investment landscape is now characterized by a fundamental shift from a focus on cost advantage to a reliance on "institutional trust". Investors are increasingly drawn to Vietnam's stable political system, predictable policy environment, and the government's concerted efforts to improve the business climate through institutional and administrative reforms. This evolution is critical for investors to understand; the country is no longer merely a low-cost manufacturing hub but is repositioning itself as a reliable and strategic partner for complex, high-value operations in the global supply chain. This is evidenced by the government's active promotion of high-tech sectors, including semiconductors, artificial intelligence (AI), and renewable energy, attracting investment from major global players.

1.2 A Pro-Investment Policy Landscape: Navigating Incentives in the Post-GMT Era

The Vietnamese government actively encourages foreign investment through a comprehensive framework of incentives codified in the Law on Investment 2020. These incentives are designed to reduce the initial financial burden on investors and promote development in priority sectors and regions. Key traditional incentives include :

-

Corporate Income Tax (CIT) Incentives: Eligible projects may receive a full CIT exemption for up to four years, followed by a 50% reduction for the subsequent nine years.

-

Preferential CIT Rates: Certain large-scale projects or those in high-tech zones or economically disadvantaged areas can benefit from a preferential CIT rate of 10% for up to 15 years.

-

Import Duty Exemptions: Machinery, equipment, and raw materials that cannot be produced domestically and are imported to create fixed assets for an investment project are exempt from import duties.

-

Land Rent Exemptions: Depending on the project's location and sector, investors may be granted an exemption from land rental fees for a period of 7 to 15 years, or even for the entire project duration in special cases.

A pivotal change in the global and local incentive landscape is Vietnam's adoption of the Global Minimum Tax (GMT) rules, effective from 2024. This international agreement, which imposes a 15% minimum tax rate on the profits of large multinational enterprises (MNEs), has the potential to neutralize the benefits of Vietnam's traditional tax-based incentives for these corporations. An MNE benefiting from a 10% preferential tax rate in Vietnam might have to pay a "top-up" tax in its home country, rendering the Vietnamese incentive moot.

Recognizing this, the Vietnamese government is strategically pivoting from tax-based incentives to a new suite of non-tax, direct financial support measures. This marks a fundamental shift in how investment support is structured and negotiated. Instead of passively applying for tax breaks, investors in high-priority sectors must now engage actively with government agencies to secure direct subsidies. These new support mechanisms include :

-

Workforce Training Support: Subsidies covering up to 50% of the actual costs for training and developing a skilled workforce.

-

Fixed Asset Investment Support: Support of up to 10% of the cost of creating fixed assets.

-

High-Tech Production Support: Subsidies of up to 3% of the value-added from producing high-tech products.

-

R&D Support: For new projects establishing R&D centers in strategic fields like semiconductors and AI, the government may provide initial cost support of up to 50%.

For prospective investors, this new reality means that an investment strategy based solely on the published tax incentives is outdated. Financial modeling and government relations strategies must now incorporate the negotiation of these direct support packages to accurately reflect the true value of investing in Vietnam.

1.3 Unparalleled Market Access: The Power of Free Trade Agreements (FTAs)

One of Vietnam's most compelling strategic advantages is its extensive network of Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). As a member of 18 FTAs, including several "new generation" pacts, Vietnam offers foreign investors an unparalleled platform for accessing key global markets with preferential terms. These agreements go beyond simple tariff reduction, creating a more transparent, predictable, and efficient trading environment.

Key agreements shaping this landscape include:

-

The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP): Provides access to a bloc of 11 Pacific Rim countries, including major markets like Canada, Japan, and Australia.

-

The EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement (EVFTA): Offers significant tariff elimination and opens up services and public procurement markets within the European Union.

-

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP): The world's largest trade bloc, connecting Vietnam with the 10 ASEAN nations plus China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand.

These FTAs provide tangible benefits for foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) operating in Vietnam, allowing them to integrate seamlessly into global value chains and export goods with reduced or zero tariffs, thereby enhancing their price competitiveness on the world stage.

Further bolstering its position in the global financial ecosystem, Vietnam's stock market was officially upgraded to "Secondary Emerging Market" status by FTSE Russell, with the change taking effect in 2026. This upgrade is a testament to the growing maturity and transparency of the country's capital markets and is expected to attract billions of dollars in new portfolio investment, enhancing liquidity and providing more sophisticated financing options for large-scale enterprises in the future.

Table 1.1: Key Benefits of Major FTAs for FIEs in Vietnam

| FTA Name | Key Partner Markets | Primary Advantage for FIEs | Strategic Implication |

| EVFTA | European Union (27 countries) | Near-total elimination of customs duties (over 99%) on goods. Improved access to EU services markets. | Ideal for manufacturers of electronics, textiles, footwear, and agricultural products targeting the high-value European consumer market. |

| CPTPP | Canada, Australia, Japan, Mexico, Singapore, etc. | Significant tariff reductions. High standards for intellectual property, labor, and environmental protection. | Positions Vietnam as a key manufacturing hub for companies looking to serve both Asian and North/South American markets under a unified rules-based framework. |

| RCEP | ASEAN, China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand | Streamlined rules of origin, allowing for more flexible sourcing of inputs within the bloc. Enhanced trade facilitation. | Strengthens Vietnam's role in regional supply chains, particularly for industries with complex production networks spanning across Asia. |

Part II: Architecting Your Corporate Structure: Legal Foundations for Success

2.1 Forms of Foreign Investment: Choosing Your Entry Vehicle

Under Vietnam's Law on Investment, foreign investors have several modalities for entering the market, each with distinct procedural, operational, and strategic implications. The choice of entry vehicle is a foundational decision that will shape the investor's experience in Vietnam.

The primary forms of investment are:

-

Direct Investment (Greenfield): This involves establishing a new economic organization from the ground up. It is the most common approach for investors with long-term plans who require full control over their operations. This can be done through:

-

A 100% Foreign-Owned Enterprise (FOE): The investor establishes a new company in which it holds 100% of the capital. This structure provides complete autonomy in management, operations, and strategic decision-making.

-

A Joint Venture (JV) Enterprise: The foreign investor partners with one or more Vietnamese domestic investors to establish a new company. While this entails sharing control and profits, a local partner can provide invaluable market knowledge, established distribution networks, and experience navigating local administrative procedures.

-

-

Indirect Investment (M&A): This involves acquiring a stake in an existing Vietnamese company by purchasing shares (for a joint stock company) or contributing capital (for a limited liability company). This can be a significantly faster route to market, providing immediate access to facilities, staff, and existing licenses. However, it necessitates comprehensive legal and financial due diligence to uncover any potential legacy liabilities, such as tax arrears, labor disputes, or litigation.

-

Business Cooperation Contract (BCC): This is a contractual arrangement between investors to cooperate on a specific business venture and share profits or products without establishing a new legal entity. This form is suitable for short-term or project-specific collaborations where the overhead and complexity of creating a new company are unnecessary. It offers flexibility but can be complex in terms of governance and liability, as these are defined purely by the contract rather than by a corporate charter.

2.2 Choosing the Right Legal Entity: LLC vs. JSC

For investors pursuing a direct investment or forming a joint venture, the two most prevalent legal entity types are the Limited Liability Company (LLC) and the Joint Stock Company (JSC). The selection between these two is not a mere legal formality but a fundamental strategic decision that dictates the company's future governance, capital structure, and exit opportunities.

-

Limited Liability Company (LLC / Công ty TNHH): An LLC is the most popular form for foreign investors in Vietnam. It can be structured as:

-

A Single-Member LLC: Owned by one organization or individual. The management structure is simple, often consisting of a Company Chairman and a Director.

-

A Multi-Member LLC: Owned by 2 to 50 members. The defining characteristic of an LLC is its relatively simple corporate structure and restrictions on the transfer of ownership interests. Members have the pre-emptive right to purchase the stake of any member wishing to exit, which helps maintain control within the founding group. This makes the LLC an ideal "control" vehicle, perfectly suited for a wholly-owned subsidiary of a foreign parent company or a closely-held joint venture where the partners want to prevent outside ownership and maintain tight governance.

-

-

Joint Stock Company (JSC / Công ty Cổ phần): A JSC must have at least three shareholders, with no upper limit. Its key features are the ability to issue various types of shares (common, preferred), freely transfer those shares (unless restricted by the charter), and raise capital from the public, including listing on a stock exchange. This structure is more complex, requiring a General Meeting of Shareholders, a Board of Management, and a Director/General Director. The JSC is a "capital and liquidity" vehicle. It is the mandatory choice for certain regulated sectors like banking and is the optimal structure for large-scale projects requiring significant capital, tech startups planning multiple funding rounds, or any enterprise envisioning an eventual Initial Public Offering (IPO) or seeking a broad base of investors.

The choice, therefore, hinges on the investor's long-term strategy. If the primary goal is to maintain absolute control over a subsidiary's operations for the foreseeable future, the LLC is superior. If the goal is growth, scalability, attracting diverse investors, and creating an easy exit path through a share sale, the JSC is the necessary choice.

Table 2.1: Comparative Analysis of LLC vs. JSC for Foreign Investors

| Feature | Limited Liability Company (LLC) | Joint Stock Company (JSC) |

| Number of Owners | 1 (Single-Member) or 2-50 (Multi-Member) | Minimum of 3, no maximum. |

| Liability | Members are liable only up to the amount of their capital contribution. | Shareholders are liable only up to the value of their shares. |

| Management Structure | Simpler: Members' Council, Chairman, Director. Suitable for direct owner management. | More complex: General Meeting of Shareholders, Board of Management, Director. Formal governance required. |

| Capital Transfer/Mobilization | Transfer of capital is restricted; subject to pre-emptive rights of other members. Cannot issue public shares. | Shares are freely transferable (unless restricted by charter). Can issue shares, bonds, and list on the stock exchange. |

| Suitability | Small to medium-sized enterprises, 100% foreign-owned subsidiaries, closely-held joint ventures. | Large-scale enterprises, companies planning to raise public capital, businesses with diverse ownership structures. |

| Typical Use Case | Manufacturing subsidiary of a foreign parent company; boutique consulting firm; family-owned business. | Tech startups, large infrastructure projects, banking and financial services, companies planning an IPO. |

2.3 Market Access Conditions: Navigating Restricted and Conditional Sectors

While Vietnam's investment environment is generally open, it is not entirely without restrictions. The government employs a "negative list" approach, meaning foreign investors can participate in any sector not explicitly prohibited or restricted. It is crucial for investors to determine where their intended business activities fall within this framework before commencing the application process.

-

Prohibited Sectors: A short list of business lines are entirely closed to all investment, both foreign and domestic. As of the Law on Investment 2020, this includes the business of debt collection services, trading in certain narcotics and chemicals, and activities related to human cloning.

-

Conditional Sectors: Many more sectors are open to foreign investment but are subject to specific conditions. The list of conditional business lines has been streamlined to 227 sectors. These conditions are designed to align with national security interests, social order, and commitments made under international treaties. Common conditions include :

-

Foreign Ownership Limits (FOLs): In certain strategic sectors, the law prescribes a maximum percentage of ownership that a foreign investor can hold. For example, foreign ownership may be capped in banking, telecommunications, or transportation services.

-

Form of Investment: Some sectors may require foreign investors to enter into a joint venture with a Vietnamese partner rather than establishing a 100% foreign-owned entity.

-

Business Scope: The scope of activities for the FIE may be limited compared to a domestic company in the same sector.

-

Sub-licenses and Approvals: In addition to the primary investment and enterprise registration, operating in conditional sectors often requires obtaining specific "sub-licenses" from relevant ministries (e.g., a trading license from the Ministry of Industry and Trade for distribution activities, a tourism license for tour operators)

-

Investors must consult Vietnam's commitments to the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the specific provisions of its bilateral and multilateral FTAs, as these international agreements often provide the most detailed and binding schedules for market access and foreign ownership limitations.

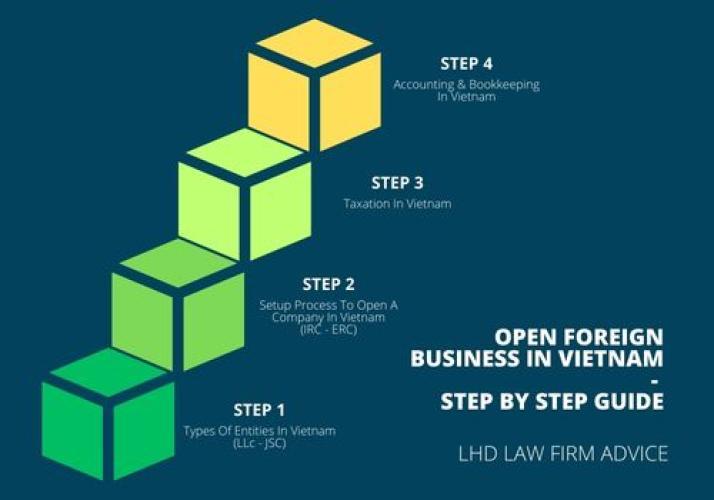

Part III: The Step-by-Step Incorporation Process: A Practical Blueprint

3.1 The Two Primary Pathways: A Strategic Overview

Establishing a foreign-invested enterprise in Vietnam typically follows one of two distinct procedural pathways, each with its own timeline, complexity, and strategic trade-offs.

-

Pathway A: Direct Investment (Greenfield) This is the standard, formal process for creating a new investment project and a new company from scratch. It is a two-stage procedure :

-

Obtain the Investment Registration Certificate (IRC): This certificate is issued by the investment licensing authority and pertains to the investment project itself. It validates the project's objectives, scale, location, and the investor's legal status and financial capacity.

-

Obtain the Enterprise Registration Certificate (ERC): Following the issuance of the IRC, the investor applies for the ERC. This certificate is issued by the business registration authority and officially establishes the legal entity (the company) that will execute the project.

-

-

Pathway B: M&A / Capital Acquisition This pathway involves a foreign investor acquiring an interest in an existing, operational Vietnamese company. The key procedural step is to obtain an Approval of Capital Contribution / Share Purchase from the Department of Planning and Investment (DPI). Once this approval is granted, the target company's ERC is amended to reflect the new foreign ownership.

While consulting firms often market a variation of the M&A route—where a Vietnamese "shelf company" is created and then sold to the foreign investor—as a faster and cheaper alternative , this approach carries significant hidden risks. The standard direct investment pathway, though potentially longer, involves a rigorous vetting of the investment project during the IRC application stage. This provides a strong legal foundation and official government recognition of the project's scope and purpose. The M&A "shortcut" bypasses this crucial project approval step for the foreign investor. While it may offer short-term gains in speed, it can lead to long-term complications, particularly when the company seeks to expand, amend its business lines, or repatriate profits, as the underlying investment project was never formally registered under the foreign investor's name. This trade-off between perceived speed and foundational legal risk is a critical strategic consideration.

3.2 Pathway A: Direct Investment - From Project to Enterprise

For investors undertaking a new project, the direct investment pathway is the most robust and legally sound method. The process is sequential and requires careful preparation of two distinct dossiers.

Step 1: The Investment Registration Certificate (IRC)

The IRC is the foundational license for any new foreign investment project. It confirms that the government has reviewed and approved the investor's plan.

-

Preparing the Dossier: The application dossier is comprehensive and must demonstrate the viability and legitimacy of the project. Key documents include :

-

Application Form for Implementation of Investment Project.

-

Project Proposal: A detailed document outlining the project's objectives, investment scale, total capital and capital mobilization plan, location, duration, implementation schedule, labor requirements, and an assessment of its socio-economic impact.

-

Proof of Investor's Legal Status: For an individual investor, a certified copy of their passport. For an organizational investor, a certified copy of its Certificate of Incorporation or equivalent.

-

Proof of Financial Capacity: This is a critical component. It can be demonstrated through audited financial statements from the last two years (for an organizational investor) or a bank balance confirmation showing funds sufficient to cover the proposed investment capital.

-

Documents for Project Location: A copy of the office lease agreement or a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) for the proposed head office and project site.

-

-

Submitting the Application: The competent authority for receiving and processing the IRC application depends on the project's location :

-

Provincial Department of Planning and Investment (DPI): For projects located outside of industrial zones, export processing zones, or high-tech parks.

-

Management Boards of Industrial Zones (IZs), Export Processing Zones (EPZs), or High-Tech Parks: For projects located within these designated zones. These boards often provide a more streamlined, "one-stop-shop" service.

-

-

Processing Time: By law, the processing time for an IRC application is 15 working days from the date of receipt of a valid and complete dossier. In practice, this timeline can be extended if the authorities request additional information or clarification.

Step 2: The Enterprise Registration Certificate (ERC)

Once the IRC has been issued, the investor can proceed to formally establish the legal entity. The ERC is the official birth certificate of the company.

-

Preparing the Dossier: The ERC application builds upon the IRC approval. Required documents include :

-

Application Form for Enterprise Registration.

-

Company Charter (Articles of Association): The constitutional document of the company, detailing its governance, management structure, and operational rules.

-

List of Members (for an LLC) or Founding Shareholders (for a JSC).

-

Copies of Legal Identification: Passports for individual members/shareholders and the legal representative(s).

-

A valid copy of the newly issued Investment Registration Certificate (IRC).

-

-

Submitting the Application: The ERC dossier is submitted to the Business Registration Office of the provincial Department of Planning and Investment where the company's head office is located.

-

Processing Time: The statutory processing time for an ERC is significantly shorter, typically within 3 to 7 working days of submitting a complete and valid dossier.

3.3 Essential Documentation & The Mandate for Consular Legalization

The incorporation process is heavily document-driven, and a single error or omission can cause significant delays. A particularly critical and often underestimated requirement is Consular Legalization. Any official document issued by a foreign authority that is to be used in an official capacity in Vietnam must undergo this multi-step authentication process to be considered valid.

The process generally involves three steps :

-

The document is first certified by a competent authority in its country of origin (e.g., a notary public).

-

It is then authenticated by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (or equivalent) of that country.

-

Finally, it is legalized by the Vietnamese Embassy or Consulate in that country.

This process does not certify the content of the document but rather verifies the authenticity of the seal, signature, and title on the document, making it legally recognizable by Vietnamese authorities. This applies to crucial documents like a corporate investor's Certificate of Incorporation, its audited financial statements, and powers of attorney. Investors must factor the time required for this process—which can take several weeks—into their project timeline.

Table 3.1: Document Checklist for FIE Incorporation (Corporate Investor)

| Document Name | Description | Key Requirements | Consular Legalization Required? |

| Business Registration Certificate | Proof of the foreign parent company's legal existence. | Must be a valid, certified copy. | Yes |

| Audited Financial Statements | Proof of financial capacity of the parent company (typically the last 2 years). | Must be audited by a recognized firm. | Yes |

| Company Charter | The charter or articles of association of the parent company. | Required to verify authority and structure. | Yes |

| Passport of Legal Representative | Identification for the individual appointed as the legal representative of the new Vietnamese entity. | Must be valid with at least 6 months remaining. A notarized copy is required. | No (Notarization is sufficient) |

| Bank Balance Confirmation | Alternative proof of financial capacity, confirming sufficient funds for the investment. | Must be issued by the investor's bank, stating a balance equal to or greater than the proposed investment capital. | Yes |

| Office Lease Agreement | Proof of the legal right to use the address registered as the company's head office. | Must be a valid lease agreement with the landlord's ownership documents. | No |

Part IV: Financial Framework: Capital, Costs, and Taxation

4.1 Understanding Capital Requirements: Charter vs. Legal Capital

Navigating Vietnam's capital requirements involves understanding two distinct concepts: Charter Capital and Legal Capital. The amounts chosen have direct implications for taxation, credibility, and regulatory compliance.

-

Charter Capital (Vốn điều lệ): This is the total value of assets that the owners (members or shareholders) commit to contribute to the company upon its establishment, as stated in the company charter. This figure is publicly recorded on the ERC. By law, investors must contribute this capital in full within 90 days of receiving the ERC. While there is no general minimum charter capital requirement for most business lines, the amount registered is not arbitrary. It serves as a public declaration of the company's financial commitment and is a key factor that banks, partners, and suppliers consider when assessing the company's credibility. Furthermore, the annual Business License Tax is levied based on tiers of registered charter capital.

-

Legal Capital (Vốn pháp định): This is a fixed, minimum amount of capital required by law to operate in certain "conditional" business sectors. This requirement is intended to ensure that businesses in sensitive or high-risk industries have sufficient financial capacity to operate safely and responsibly. Examples of sectors with legal capital requirements include :

-

Real Estate Business: 20 billion VND

-

Audit Services: 5 billion VND

-

Labor Sub-leasing Services: 2 billion VND

-

Commercial Banks: 3,000 billion VND For any business operating in these sectors, the registered charter capital must be equal to or greater than the prescribed legal capital

-

Investors often face the temptation to register a minimal charter capital to reduce the annual license tax. However, this is a short-sighted strategy. Under-capitalizing a company can create significant operational and strategic challenges. A company with a registered capital of a few thousand dollars will struggle to secure loans, win large contracts, or be taken seriously by government agencies. It also limits the amount of equity that can be injected into the business without undergoing a formal and time-consuming capital increase procedure. A more prudent approach is to set a charter capital that realistically reflects the company's operational needs for the first one to two years, balancing tax efficiency with commercial credibility and financial flexibility.

4.2 Budgeting for Establishment: A Realistic Cost Overview

The costs of establishing a company in Vietnam can be divided into two main categories: government fees and professional service fees.

-

Government Fees: These are relatively low and cover administrative charges for issuing licenses and making public announcements.

-

Professional Service Fees: This constitutes the majority of the establishment cost. Due to the complexity of the procedures, the language barrier, and the need for precise documentation, most foreign investors engage law firms or consulting agencies. These firms handle the entire process, from advising on the optimal structure to preparing and submitting all applications and following up with the authorities.

The total cost varies depending on the complexity of the project, the chosen pathway, and the service provider. Market data indicates the following ranges :

-

M&A Pathway (Transfer from a Vietnamese entity): This is often presented as the more cost-effective option, with service fees typically ranging from 15,000,000 VND (~$600 USD) to 23,000,000 VND (~$900 USD), depending on the region.

-

Direct Investment Pathway: This more formal process is generally more expensive due to the additional IRC application step. Costs can range from 25,000,000 VND (~$1,000 USD) to 30,000,000 VND (~$1,200 USD) for standard business lines.

-

Conditional or Complex Sectors: For business lines that require additional sub-licenses or have more complex requirements (e.g., retail, manufacturing, logistics), costs can be significantly higher, potentially ranging from $1,700 USD to over $3,000 USD.

These figures are for the core incorporation service. Investors should also budget for ancillary costs such as document translation, notarization, consular legalization, and the initial post-establishment compliance tasks.

4.3 The Corporate Tax Regime: An Introduction

Upon establishment, an FIE becomes subject to Vietnam's tax system. A basic understanding of the primary corporate taxes is essential for financial planning and compliance.

-

Corporate Income Tax (CIT): The standard CIT rate in Vietnam is 20% on taxable profits. As discussed in Part I, preferential rates (e.g., 10%, 15%, 17%) and tax holidays (exemptions and reductions) are available for projects that meet specific criteria for location, industry, or scale.

-

Value-Added Tax (VAT): VAT is applied to the value added to goods and services at each stage of production and circulation. The standard rate is 10%. A rate of 0% is applied to exported goods and services, which is a significant advantage for export-oriented manufacturers. Certain essential goods and services are exempt from VAT.

-

Business License Tax: This is an annual fixed tax paid by all enterprises. The amount is based on the company's registered charter capital :

-

Charter capital over 10 billion VND: 3 million VND/year.

-

Charter capital of 10 billion VND or less: 2 million VND/year.

-

Branches and representative offices: 1 million VND/year.

-

-

Other Potential Taxes: Depending on the specific business activities, an FIE may also be liable for other taxes, such as :

-

Import/Export Duties: Levied on goods crossing Vietnam's borders.

-

Special Consumption Tax (SCT): Applied to certain "luxury" goods and services like spirits, automobiles, and cigarettes.

-

Environmental Protection Tax: Levied on products that can cause negative environmental impacts, such as petroleum and coal.

-

Part V: From License to Launch: Post-Establishment Essentials

Receiving the Enterprise Registration Certificate (ERC) marks the legal birth of the company, but it does not mean the company is ready for business. A series of critical, mandatory administrative tasks must be completed immediately to ensure the company is fully operational and compliant with Vietnamese law. Failure to complete these steps can result in significant fines and operational disruptions, such as a frozen tax code.

5.1 The "First 30 Days" Compliance Checklist

The period immediately following incorporation is crucial. The new company's management must prioritize the following tasks, most of which have strict deadlines.

-

Make the Company Seal (Dấu tròn): While the Law on Enterprises 2020 gives companies more flexibility regarding the use of a physical seal, it remains a practical necessity for most official transactions, particularly when dealing with banks, government agencies, and signing official contracts.

-

Display the Official Company Sign: A physical sign bearing the company's official name and tax code must be installed and displayed at the registered head office address. This is a mandatory requirement, and tax authorities often conduct physical checks. Failure to comply can lead to penalties and the suspension of the company's tax code.

-

Open Company Bank Accounts: This is a two-fold process:

-

Direct Investment Capital Account (DICA): This is a special-purpose foreign currency account used exclusively to receive capital contributions from foreign investors and to remit profits and principal abroad. All capital must flow through this account.

-

Current Account: A regular VND transaction account for handling domestic payments and receipts.

-

-

Contribute Charter Capital: The foreign investor must transfer the committed charter capital from their overseas bank account into the newly opened DICA within 90 days of the ERC issuance date.

-

Initial Tax Registration: The company must register with the local tax authority managing its district. This involves submitting a dossier that includes the appointment decision for the Director and Chief Accountant, and registering the company's chosen accounting method (e.g., under Circular 200 or Circular 133) and VAT calculation method (deduction or direct method).

-

Declare and Pay Business License Tax: The company must submit its business license tax declaration and pay the tax for the first year. The deadline is January 30th of the year following the year of establishment.

-

Procure a Digital Signature (USB Token): A digital signature is mandatory for all electronic transactions with government agencies in Vietnam. It is used for submitting online tax returns, customs declarations, and social insurance filings.

-

Register for and Issue Electronic Invoices (Hóa đơn điện tử): All businesses in Vietnam are required to use electronic invoices. The company must register its e-invoice template and provider with the tax authorities before it can legally issue an invoice to a customer.

5.2 Ongoing Operational Compliance

Beyond the initial setup, investors must establish systems for ongoing compliance from day one. Key areas include:

-

Accounting System: The company must establish an accounting system that complies with Vietnamese Accounting Standards (VAS). All books and records must be maintained in Vietnamese Dong (VND) and, if necessary, also in a foreign currency.

-

Labor and Social Insurance: As soon as the company hires its first employee under a labor contract, it must register with the social insurance authorities. The company is required to contribute to social, health, and unemployment insurance funds for its employees.

-

Investment Project Reporting: The company must adhere to the periodic reporting requirements stipulated in its IRC. This typically involves submitting quarterly and annual reports to the Department of Planning and Investment on the progress of the investment project.

Table 5.1: Checklist of Mandatory Post-Establishment Tasks and Deadlines

| Task | Responsible Body / Vendor | Deadline | Critical Importance / Penalty for Non-Compliance |

| Display Company Sign | Company Management | Immediately after receiving ERC | Mandatory. Fines and potential suspension of tax code. |

| Open DICA & Current Account | Commercial Bank | Within the first week | Essential for capital contribution and operations. Capital cannot be legally received without a DICA. |

| Contribute Charter Capital | Foreign Investor | Within 90 days of ERC issuance | Mandatory. Failure can lead to fines and potential forced reduction of registered capital. |

| Declare & Pay License Tax | Local Tax Authority | Jan 30th of the year following establishment | Mandatory. Fines for late submission and payment. |

| Procure Digital Signature | Authorized Vendor | Within the first 1-2 weeks | Required for all online tax and social insurance filings. Operations are impossible without it. |

| Register for E-Invoices | Local Tax Authority | Before issuing the first invoice | Illegal to conduct sales without registered e-invoices. |

| Register Employees for Social Insurance | Social Insurance Authority | Within 30 days of signing the first labor contract | Mandatory. Significant fines and back-payment with interest for non-compliance. |

Part VI: Strategic Outlook: Mitigating Risks and Ensuring Long-Term Success

6.1 Common Operational Challenges and Risks

While Vietnam presents a compelling investment case, foreign investors must be prepared to navigate a unique set of operational challenges and risks to ensure long-term success. A realistic understanding of these potential hurdles is crucial for effective planning and risk mitigation.

-

Bureaucracy and Regulatory Ambiguity: Despite significant improvements, Vietnam's administrative procedures can still be complex, time-consuming, and occasionally opaque. Investors may encounter "grey areas" in the law where interpretation is not always clear, requiring careful navigation and often professional legal advice.

-

Infrastructure Gaps: Major cities and industrial hubs boast modern infrastructure, but logistical bottlenecks and underdeveloped transport links can be a challenge in more remote areas, potentially impacting supply chain efficiency.

-

Intellectual Property (IP) Protection: Vietnam has a legal framework for IP protection that aligns with international standards. However, enforcement remains a significant concern. Counterfeiting and piracy are prevalent, requiring businesses to adopt a proactive IP strategy that includes registering trademarks and patents in Vietnam and being prepared to take enforcement action.

-

Human Resources Constraints: There is a growing pool of young, educated labor, but a shortage of highly skilled technicians, experienced middle managers, and senior executives persists. Competition for top talent is fierce, and investors may need to invest heavily in training and development.

-

Corruption: The Vietnamese government has launched a vigorous anti-corruption campaign, but corruption remains a risk in business dealings. Investors must adhere to strict internal compliance policies and be aware of the risks associated with facilitation payments or other illicit practices.

-

Cultural and Language Differences: The difference in business culture can affect negotiations, management styles, and customer relations. While English is increasingly common in the business community, a language barrier still exists, often necessitating the use of translators and interpreters for critical communications.

6.2 A Critical Warning: The Perils of Nominee Structures

In an attempt to circumvent foreign ownership limits in conditional sectors or to simplify the establishment process, some investors are tempted to use a "nominee structure." This involves having a Vietnamese national legally register as the owner of the company, while a private side-agreement states that the foreign investor is the true beneficial owner.

This practice must be unequivocally discouraged as it is a direct path to the potential total loss of investment. Under Vietnamese law, such nominee arrangements are legally void (vô hiệu). The individual or entity whose name appears on the Enterprise Registration Certificate is the sole legal owner of the company and its assets. The side-agreement is typically unenforceable in a Vietnamese court.

The risks are catastrophic :

-

Total Loss of Control: The nominee has complete legal authority to sell the company's assets, take on debt, or transfer ownership to a third party without the foreign investor's consent.

-

No Legal Recourse: In the event of a dispute, the foreign investor has no legal standing as an owner and cannot sue to reclaim their investment. The capital provided is effectively treated as an unsecured, undocumented loan to the nominee.

-

Liability without Ownership: In the case of bankruptcy or legal trouble, the nominee is the legally responsible party, but the foreign investor stands to lose their entire financial contribution.

The perceived convenience of a nominee structure is a dangerous illusion that masks a complete abdication of legal ownership and control. It is not a calculated risk but a fundamental flaw in the investment structure that should be avoided under all circumstances.

6.3 Key Legal Considerations for Sustainable Operation

Beyond the initial setup and common challenges, long-term success in Vietnam requires ongoing attention to several key legal areas.

-

Land Use Rights: Foreign investors cannot own land in Vietnam. Instead, the state grants Land Use Rights (LURs) for a specific period, typically 50 years, which can be extended up to 70 years in certain cases. For manufacturing, real estate, or agricultural projects, securing stable, long-term LURs is a critical component of the investment.

-

Labor Law Compliance: Vietnam's labor code is comprehensive and generally protective of employee rights. Investors must ensure strict compliance with regulations regarding labor contracts, working hours, overtime, termination procedures, and mandatory social insurance contributions to avoid disputes and legal penalties.

-

Profit Repatriation: Foreign investors are legally entitled to remit their profits abroad. However, this process is strictly regulated. Profits can only be transferred annually after the company has fulfilled its corporate income tax obligations and submitted its audited annual financial statements to the tax authorities. The process can be document-intensive, requiring proof that the profits are legitimate and that all taxes have been paid.

-

Dispute Resolution: While disputes can be settled in Vietnamese courts, the process can be slow. For significant commercial contracts, particularly with other foreign entities, it is common and advisable to include a clause specifying international arbitration (e.g., at the Singapore International Arbitration Centre - SIAC) as the preferred method for dispute resolution. This provides a more neutral and often more efficient forum for resolving disagreements.

0 comment